“. . . science may tell us how to deal with human behavior, but just what is to be done must be decided in an essentially non-scientific way.”

Skinner, B F (1953) Science and Human Behavior

One may raise eyebrows at beginning any discussion on behavioural science with a quote from the founder of Behaviourism BF Skinner. But in some ways, he was at the heart of the debate on the place of science in the study of human behavior, and whether it is possible – never mind ethical – to subject human behavior to scientific scrutiny. After all, humankind is not a laboratory rat or a Pavlovian dog.

The study of human behavior in a business context has come a long way since those somewhat crude studies using rats and pigeons tried to extrapolate their findings to people. Yet the principles of behaviorism – classical stimulus-response conditioning, notions of reward and punishment, and so on – are still evident in much of what we do today in the office and on the factory floor.

Take compensation – wages and benefits – as an example. Often thought to be the primary incentive for employees, it is practically impossible to pin down pay as a true motivator. Hourly-paid workers, who comprise two-thirds of the American workforce and slowly rising since the 1970s, tend to see their wage as the more tangible aspect of why they work. One reason is that it is more easily manipulated with overtime – the worker has some measure of control over it.

However, there are some disadvantages to getting paid by the hour. Hourly workers typically have less job security, worse pay and worse benefits than salaried workers. For example, they often have worse health care coverage and less vacation time. During recessions, their employers can cut the number of hours they work, reducing their pay further. Hourly workers also can get fired without cause or with short notice.

The difficulty with focusing on pay as a motivator has a long history. At the forefront of attempts to put pay in context is Frederick Herzberg, whose survey study in 1959 helped him formulate a fundamental truth about behavioral science which, in the absence of any serious challenge, continues effectively to validate it. He concluded that the factors which motivate people at work are different to and not simply the opposite of the factors which cause dissatisfaction:

“We can expand … by stating that the job satisfiers deal with the factors involved in doing the job, whereas the job dissatisfiers deal with the factors which define the job context.”

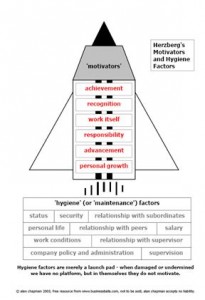

Herzberg’s research showed that certain factors truly motivate (‘motivators’), whereas others tended to lead to dissatisfaction (‘hygiene factors’).

According to Herzberg, Man has two sets of needs; one as an animal to avoid pain, and two as a human being to grow psychologically.

According to Herzberg, Man has two sets of needs; one as an animal to avoid pain, and two as a human being to grow psychologically.

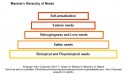

There are parallels to Herzberg in Abraham Maslow’s earlier work on motivation theory, his Hierarchy of Needs. Herzberg’s ‘motivators’ (achievement, recognition, etc.) find their parallel in Maslow’s self-actualization, and his ‘hygiene factors’ can be slotted in at different levels of the hierarchy (e.g., status = Level 4, esteem needs; security = Level 2, safety needs, etc.).

If one wants to track back to the start of modern behavioral science (although it wasn’t called that at the time), one needs to look no further than Frederick Taylor and his theory of ‘scientific management’ in 1909. To be honest, Taylor was less interested in the people doing the work than in optimizing and simplifying jobs, in studying how work was performed and its effect on productivity. Taylor was the original ‘time and motion’ studies man.

Some of his principles – so successfully applied on the Ford assembly lines – still ring true today, amongst them being to match workers to their jobs based on capability and motivation, job training, performance monitoring, and an understanding of the roles of management, supervision, and employees.

However, more recent approaches to behavioral science such as Management by Objectives (MBO), Continuous Improvement (kaizen), and Business Process Reengineering (BPR) have surpassed Taylorism by promoting individual responsibility and pushing decision-making throughout the organization.

What has become apparent from the second half of the twentieth century, starting with Maslow and Herzberg and McGregor, is an increasing emphasis on the ethics of good management. Maslow introduced the terms humanistic psychology and transpersonal psychology and even wrote a book called The Psychology of Science, the first such to twin these two terms.

As management becomes more transparent, participative, inclusive, and open to change, and as work becomes more specialized, the boss/subordinate dichotomy has been eroded. Forward-thinking organizations these days talk about the ‘Psychological Contract’ between worker and manager. The Psychological Contract is quite different to a physical contract or document – it represents the notion of ‘relationship’ or ‘trust’ or ‘understanding’ which can exist for one or more employees, instead of a tangible piece of paper or legal document.

“…the employment relationship consists of a unique combination of beliefs held by an individual and his employer about what they expect of one another…”[1]

How work has changed since the 1980s

| Up to 1980s | After the 1980s |

| work teams | virtual teams |

| factory/office working | home/mobile-working |

| line management | matrix management |

| customer service | call centers |

| in-house services | outsourcing and off-shoring |

| job for life | job for two years |

| a life’s work | a career for ten years |

| onsite services | online services |

| few employee rights | many employee rights |

| low employee awareness | high employee awareness |

| employees isolated | employees connected |

| reliable pensions | unreliable pensions |

| Other issues: equality, discrimination, training, qualifications, share-save, pensions, buy-to-let, 4x4s, telephone, letters, mainframe computers and terminals, sub-contracting, employment contracts | Other issues: life-balance, sabbaticals, lifelong-learning, employee ownership, community, social enterprise, email, social networking, mobile web, globalization, the psychological contract |

______________________________

[1]Michael Armstrong (2006). Handbook of Human Resource Management Practice (10th Ed.)

Perhaps the most crucial difference between the behavioral and all other sciences is the fact that the subject matter of the former possesses insight and intelligence. The pressing questions are no longer about how to investigate but what to investigate and what to do with what we discover, questions that science alone cannot answer. In many respects we are back once more in the realms of philosophy, from which science originally emerged, to help us answer those most difficult but essential questions.